The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is getting ready to study the amazing light displays on the big planets Uranus and Saturn.

Two groups of astronomers from the University of Leicester will use the $10-billion telescope to observe the auroras on Saturn and Uranus. They want to learn more about how these colorful light shows occur on different planets.

Henrik Melin, from the University of Leicester School of Physics and Astronomy, will lead the study on Uranus. He said, “The JWST is changing how we see the universe, from our own solar system to the earliest galaxies. I’m excited to use this amazing telescope to learn more about Saturn and Uranus.”

Auroras, like the Northern and Southern Lights seen on Earth, are beautiful light displays that happen near the poles.

These colorful lights happen when particles from the sun’s solar wind hit Earth’s magnetic field. They travel along the magnetic field lines and interact with the particles in our atmosphere, creating glowing light.

When the sun sends out a lot of plasma in coronal mass ejections, auroras become brighter and can be seen even in places farther away from the poles on Earth.

While auroras have been spotted on other planets with atmospheres and magnetic fields, not much is known about these glowing displays on other worlds.

We still have limited knowledge about the auroras on Uranus, a chilly planet made mostly of water, ammonia, and methane.

Just last year, a team from the University of Leicester confirmed the existence of an infrared aurora on Uranus after studying it for thirty years. The planet is unique because it’s tilted almost sideways due to a past collision with a large object. This means its poles face almost directly toward and away from the sun, and its auroras appear near what would typically be the equator on other planets.

As Melin and his team use the JWST to study the auroras on Uranus, they’re looking into something hinted at by previous discoveries: Could these auroras be the reason Uranus is warmer than scientists expected?

“Gas giant planets like Uranus are much hotter than they should be based on sunlight alone,” Thomas explained last year. “One idea is that the powerful auroras on these planets might be heating them up by pushing heat from the auroras toward the magnetic equator.”

The JWST will start studying Uranus early in 2025. It will take pictures of the ice giant during a single day on the planet, which is about 17 Earth hours long. This will help the team map out the auroras across Uranus’ magnetic field as it rotates.

The scientists also want to find out if the auroras on Uranus happen when its magnetic field interacts with the solar wind, like it does on Earth. Or, if the charged particles that cause the auroras come from within the Uranian system, similar to how Jupiter makes its auroras. It’s also possible that Uranus’ auroras are caused by a combination of these things, like Saturn’s auroras.

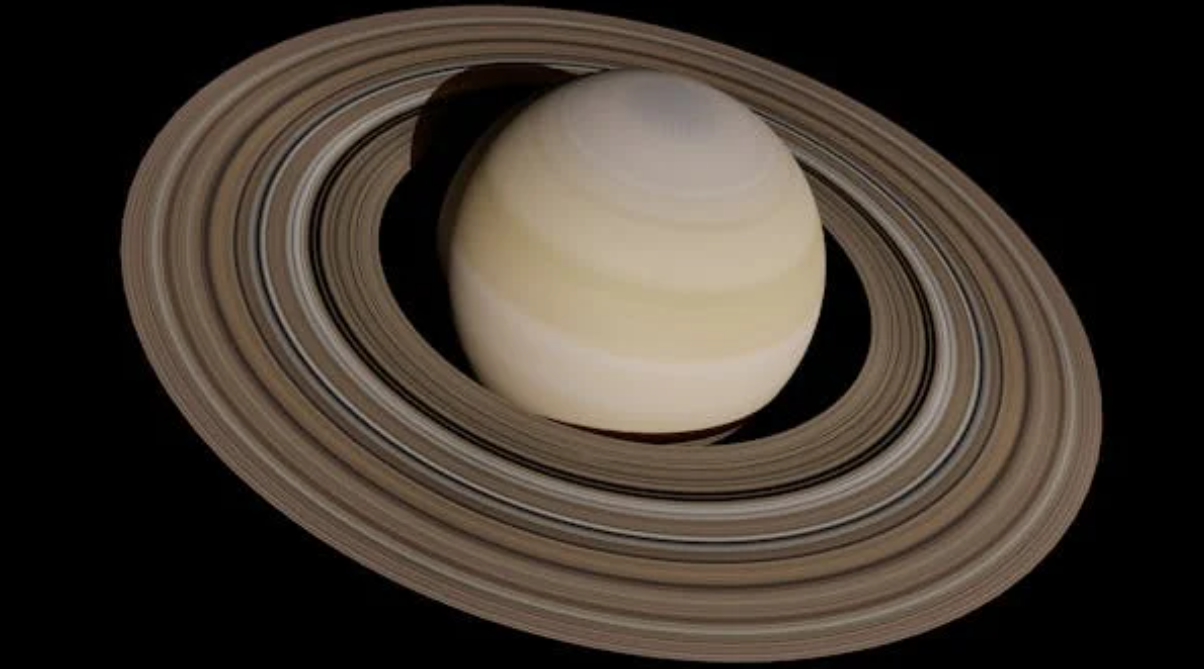

The JWST Saturn aurora project, led by scientist Luke Moore from Boston University Center for Space Physics, will observe Saturn’s northern auroral region for a whole Saturnian day, which lasts about 10.6 hours. This will help the team see how the temperature changes in this region as Saturn spins.

By studying Saturn’s atmospheric auroral energies for the first time, the team hopes to learn more about where the charged particles in Saturn’s atmosphere come from and how they create the auroras.

Both JWST studies of the giant planets will use the very sensitive Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) instrument.

Once scientists have this information, they can understand better how auroras are made in our solar system and how they affect Earth. They might also be able to learn about auroras on planets outside our solar system, called exoplanets.

“Most exoplanets we’ve found are like Neptune and Uranus in size. They might have similar magnetic fields and atmospheres,” said Thomas. “Studying Uranus’s aurora helps us understand the atmospheres and magnetic fields of these planets, and whether they could support life.”